Textiles:

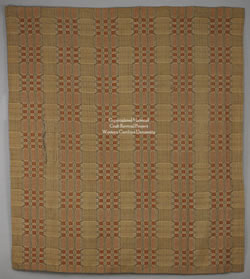

Coverlets

Typically, it took a single weaver six full days to complete a coverlet. But that did not include the preparation of material, which began a half-year earlier. Coverlets were made from wool, cotton or flax, so craftsmen had to first raise and sheer sheep, grow and card cotton, or harvest and ret flax. Before weaving could begin, the harvested and cleaned material was spun into thread.

Many coverlets were not made from a single material, instead, combinations were used to serve varied purposes of warmth and durability. In the mountains the most popular combination was a coverlet made from flax and wool. Flax was the plant used to produce linen, a strong material that allowed a coverlet to last for years, even with everyday use. After growing, preparing, and spinning, the flax thread was strung onto a loom. Wool was woven over linen to provide warmth. A coverlet made from linen and wool was called linsey-woolsey. Usually, coverlets were made from different colored threads that resulted in a variety of patterns with poetically descriptive names.

Much of the scholarship on the Craft Revival focuses on whether or not the Revival changed cultural forms. One change that occurred concerned the finishing of a coverlet. In a mountain home, the loom used to weave a coverlet was typically forty-four inches wide, so to make a full bed cover, a weaver had to piece together the two lengths of woven fabric. This created a seam down the middle of the coverlet. Before the revival, especially among families who made coverlets primarily for warmth, matching the central seem was not an issue. A thrifty craftsman would not think of weaving an extra length of fabric only to cut off part of it to achieve a matched seam. During the revival, however, having the coverlet “hit the seam” was considered a sign of good craftsmanship.

See More: Coverlets, Counterpanes