Textiles:

Weaving

An overshot coverlet was made with a woolen weft (the crosswise threads) woven onto a cotton warp (the lengthwise threads). A popular variation, in which wool thread was woven onto a linen warp made from flax, was known throughout the region as linsey-woolsey. Another type of coverlet was the counterpane. More rare than coverlets, counterpanes--called dimities in some localities—were a cotton-on-cotton weave and usually solid in color.

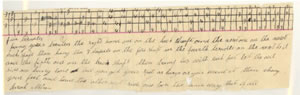

A weaving pattern was recorded on a draft, a strip of paper with marks indicating changes the weaver had to make to reproduce a particular coverlet pattern. Drafts varied from four inches to half a yard long, depending on the length of a pattern block. Old drafts often are found pierced with small holes. If a baby or cooking pot needed attention, a weaver — interrupted — marked her place in the pattern with a straight pin.

Woven on a loom, a coverlet was made from two layers of perpendicular threads. The first layer, strung lengthwise onto the loom, is called the warp. Typically, a coverlet required some 700 to 800 warp threads. Each had to be strung onto the loom and threaded into the loom’s heddle. A second thread was wound around a hand-held shuttle. With the heddle picking up some of the warp threads, the weaver threw the shuttle across the width of the loom, going over-and-under alternate warp threads. This over-under action created the interlocking weave that made a strong and useful coverlet.

There were two types of looms used in the Southern Highlands. The traditional mountain loom was constructed of heavy timbers and took up a lot of floor space. While some favored the traditional mountain loom for its authenticity, others focused on the practicality of using a smaller, lighter-weight loom. Josephine Mast and her sister Mrs. Robert Mast worked on looms passed down in their family. Weaving in Valle Crucis, North Carolina, the Mast sisters took pride in the fact that their looms had been in use for more than a hundred years. But others favored smaller, manufactured lightweight looms for their practicality. By the 1920s, Kentucky’s Berea College was already a major weaving center. Berea’s Fireside Industries program not only sold finished weavings, but produced looms for sale as well.

During the 1930s the Southern Highland Handicraft Guild, a regional cooperative marketing association formed to promote the sale of crafts, polled their members to see how many looms were in operation in the mountains. In western North Carolina, the guild counted 40 looms at the Crossnore School near Weaverville, 16 under the direction of the Spinning Wheel in Asheville, and 40 maintained by the Penland Weavers. The John C. Campbell Folk School operated a number of looms, but eventually shifted the focus of their craft production to woodcarving. The Craft Revival in Appalachia did not operate in isolation. A similar interest in handwork and preservation was occurring in other parts of the country. Looms were made and shipped from New Hampshire, upstate New York, and Michigan. Closer to western North Carolina, Ely McCarter, a mountain woodworker, made and sold looms from Gatlinburg, Tennessee in the heart of the Great Smoky Mountains.

See More: Woven Items, Looms