People: Bigmeat Family

The Bigmeat name is synonymous with high-quality Cherokee pottery. Matriarch Charlotte Welch Bigmeat (1887–1959) was steeped in the pottery tradition. Her sister-in-law Maude Welch, also an acclaimed potter. Charlotte and her husband, Robert Bigmeat, raised five daughters and a son on Wrights Creek in the Painttown section of the Qualla Boundary. Each of her five daughters—Tiney, Ethel, Elizabeth, Mabel and Louise—also became potters. Between them, they were taught pottery, demonstrated at the Oconaluftee Indian Village, and were active in Qualla Arts and Crafts Mutual. Over the years, the Bigmeat family created pottery with a signature style and standard, including an Indian head pot made by Charlotte Bigmeat that was later reproduced by her daughters. “In its final form, perfection, quality, and tradition are our standards,” said Louise Bigmeat Maney, youngest daughter and most experimental in her pottery of all the sisters. Cherokee potter Joel Queen continues the Bigmeat legacy; Ethel Bigmeat was his paternal grandmother.

Charlotte Welch Bigmeat (1887–1959) was steeped in the pottery tradition. Through marriage, she was related to Maude Welch, who was married to Charlotte’s brother, Will. Her youngest daughter claimed their family history included turn-of-the century potter Iwi Katalsta (Eve Catolster). When Charlotte married Robert Bigmeat, she forever made the Bigmeat name synonymous with high-quality Cherokee pottery. Writing about the Bigmeat family always includes speculation on their name. Its derivation has been proposed to mean “big meeting place” and alternately an indication that the family raised beef, which would have been a distinctive profession among a people whose traditions depended on hunting and fishing. Charlotte Bigmeat influenced Cherokee’s pottery tradition through the skills of her potter-daughters: Tiney, Ethel, Elizabeth, Mabel and Louise. She raised her daughters and a son on Wrights Creek in the Painttown section of the Qualla Boundary.

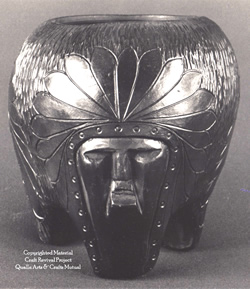

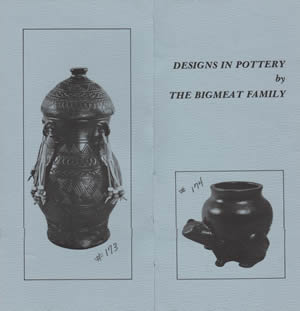

Indian head pot |

Seven-sided peace pipe |

Sisters-in-law Charlotte Bigmeat and Maude Welch must have formed an impressive duo dominating the pottery market in Cherokee. The sisters-in-law attended the earliest discussions about forming an artisan association in Cherokee; as the project moved forward, they were joined by the younger generation, Charlotte’s daughters Elizabeth and Tiney. Over the years, the family created pottery with a signature style and standard. An Indian head pot was one form that was made by the elder Bigmeat and later reproduced by her daughters. This small bowl appealed to the growing tourist trade, its “Indian” motif a memento of a visit to Cherokee. The bowl was polished to a high sheen to create a smooth surface for the design applied to its side. The stylized feathered headdress was drawn onto the body of the pot by incising. Another pottery form often produced by the Bigmeat family was the seven-sided peace pipe. This piece was finished with a surface treatment known as a bark design for its resemblance to tree bark. The pipe’s seven arms represent the seven Cherokee clans. The pot does have some precedent in archeology, but its protrusions are exaggerated from the original. The words of Louise, Charlotte Bigmeat’s youngest daughter, sum up the family’s approach: “In its final form, perfection, quality, and tradition are our standards.”1

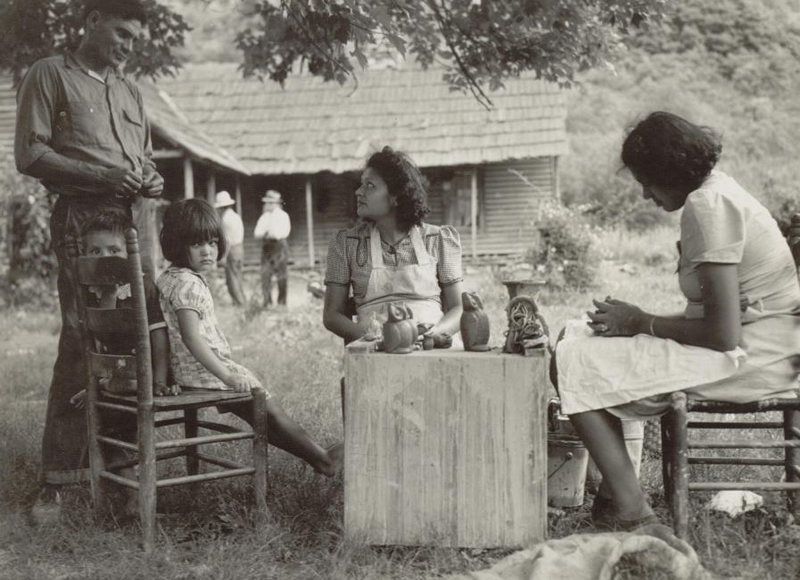

All of Charlotte Bigmeat’s daughters made pottery at one time or another and acknowledged that it was an “activity of hard work.” Tiney Bigmeat Thompson (1913–1999) was the oldest of Charlotte Bigmeat’s daughters. Ethel Bigmeat Queen (1916–1942) was the next daughter born into the family. A photograph of Ethel posed with a selection of Cherokee crafts shows owls similar to ones pictured in a 1940s-era photograph of sisters Tiney and Elizabeth working in their yard. These forms have a precedent, although the owls made by the Bigmeats were more stylized than prehistoric owl effigies. Cherokee potter Joel Queen continues the legacy of Ethel Bigmeat, his paternal grandmother. He recalled that his grandmother gathered clay from the riverbank on Macedonia Road, shoveling it out of a huge pit and carrying it four miles back to her house in metal pails. He attempts to follow her tradition, collecting clay once a year, drying it in ten-pound cakes in preparation for a year of making his own pottery.2

Ethel Bigmeat, Photograph courtesy of UNC-Chapel Hill

Like many Cherokee craftsmen, the Bigmeats worked outdoors. One of the sisters recalled that they usually worked under a large maple tree in the yard. Later, when their mother wanted a shop, their father built one for her. From town, a guide would take tourists to various artisans’ homes, where they would be able to purchase crafts directly and, perhaps, watch them being made.

Elizabeth (left) and Tiney Bigmeat working at their home on Wrights Creek

Photograph courtesy of the Great Smoky Mountains National Park

As adults, Elizabeth “Lizzie” Bigmeat Jackson (1919–2008) and sister Mabel Bigmeat Swimmer (1925–1991), both moved away from North Carolina to Flint, Michigan, where they continued to make pottery. They regularly brought home carloads of their pottery to fire and sell at local craft shops. Before moving north, Mabel demonstrated for visitors at the Oconaluftee Indian Village and expressed her interest in pottery making within the context of a sustainable culture. “I enjoy doing this work,” she said, “and hope that it will continue to be a part of our Cherokee culture in the years ahead.”

Elizabeth “Lizzie” Bigmeat Jackson |

Blackware bird lamp by Elizabeth Bigmeat Jackson |

Blackware water pipe by Elizabeth Bigmeat Jackson |

Mabel Bigmeat demonstrating at the Oconaluftee Indian Village |

Blackware vase with bear paw imprint by Mabel Bigmeat Swimmer |

Pottery vase by Mabel Bigmeat Swimmer |

In 1979, Qualla Arts and Crafts Mutual hosted an exhibition of the work of three of the Bigmeat sisters: Elizabeth Bigmeat Jackson, Mabel Bigmeat Swimmer and Louise Bigmeat Maney. The exhibition noted that the “Bigmeat sisters each has developed her own individual methods of firing, coloring, and applying surface designs.”3 A photograph, most likely made by the Indian Arts and Crafts Board, shows a coiled and modeled blackware water pipe by Lizzie Jackson. The base of the pipe is incised with a friendship pattern; along its sides are two modeled lizards. Another form made by Lizzie Jackson was an oil lamp with a shallow stable bowl used to hold oil. The handle of this particular oil lamp has been shaped into the form of a bird. A pot with a totemic figure, such as this one, is also called an effigy pot. To make this piece, earthenware clay was shaped using the coil method and then burnished, before carving and incising the details of the bird’s head into the clay. The sisters acknowledged that the extra income from their pottery helped support the family. Later, as Lizzie’s work matured and she realized the value of her creative gift, she remarked, “Today, the money is not as important as the pleasure that I get from my work.”

The youngest of Charlotte Bigmeat’s daughters, Louise Bigmeat Maney (1932–2001) was, certainly, the most experimental. Louise started out like her sisters, learning pottery from their mother. As the youngest, she began working in clay when she was just six or seven years old. When she was eight, she told her mother that she was “never going to make pottery because we had to work so hard at it.” What sounded like a child’s complaint actually came to pass as Louise struggled with her cultural identity. “It seemed like anything Indian was not okay,” she said, explaining her experience in school. Still, she continued to assist with the pottery until her mother died, when Louise abandoned pottery altogether. “The period following my mother’s death was a non-active time as far as my artwork was concerned. Child rearing, education and helping to provide for a family of seven children took precedence over art and much of my time and energy.”

Louise Bigmeat married John Henry Maney (born 1931). Also from Painttown, Maney was descended from a family of well-known basket weavers that included Nancy and Rowena Bradley. After all of the couple’s seven children were enrolled in school, Louise went back to school as well. She finished high school and went on to take college courses during summer. She expanded her skills and education by taking courses at Haywood Community College, Western Carolina University, and the Institute of American Indian Arts. She focused on art and art education, learned how to throw on the potter’s wheel, and mastered the science of mixing glazes. This experience, no doubt, broadened her repertoire of forms and introduced her to other potters. For more than twenty years, Louise Bigmeat Maney worked as an educator; still, she continued to struggle with cultural conflict. Finding the school curriculum lacking, she brought in clay and taught the children how to make beads. Instead of enjoying her contribution, she felt she was “doing something against the rules.” In the late 1950s, Louise Bigmeat Maney returned to her roots as a potter, acknowledging the influence of her mother.

All I know I learned from her, more than I learned in school. …We learned to read and write at school, but I learned all my culture from her when I was small. …I am now doing what I really want to do and had wanted to do all along, but turned my back on when I was younger. Pottery is my main source of life now. I enjoy what I’m doing. I have put myself into being a potter …and what I can do best is pottery. I learned it when I was a small child. That was my gift. …Creating pottery is a part of me.4

Louise Bigmeat Maney at groundbreaking for the Folk Art Center |

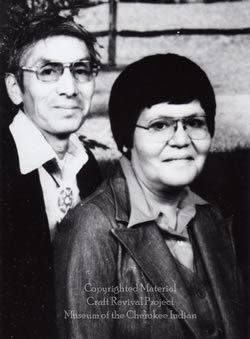

John and Louise Maney |

Blackware pottery vase by Louise Bigmeat Maney |

When she returned to making pottery, her husband joined her, and together they introduced modern production methods into their practice and established the Bigmeat House of Pottery at the entrance to Painttown. “John Henry got interested in helping me. … Making pottery completely by hand took too much time, so we bought a wheel. Now John Henry does all the pottery-turning and the firing. I do the decorating and shaping.”

One characteristic of Bigmeat Pottery is its distinctive black color, the result of smoking the clay. In spite of the high level of breakage, the Maneys fired their pottery in a large drum. Maney explained their process: “John Henry does the firing in a large drum. If the drum is sealed, the pottery gets a smoky or black color. Leaving the can open completely like the ancient Indians did makes the pottery come out with a combination of black and the natural color of the clay.” In 1976, she and John Henry were part of a Documentary of Six Cherokee Artists, an exhibition organized to inaugurate the opening of a new members gallery at Qualla Arts and Crafts Mutual. The exhibition brochure named them “two of the most competent potters in the Cherokee Indian Tribe.”

Besides their use of the wheel, the artist team was innovative and experimental. Louise worked out designs for their pottery on paper and then transferred these designs onto the pottery surface. Both Maneys did some throwing, but they returned to their Cherokee roots when it came to “designing, carving, polishing, and firing,” or so Louise claimed. In reality, the Maneys continued to experiment with pottery forms, creating unique objects, like a pedestal bowl with deep carvings and a burial urn with added dangles of beads. In addition to their retail operation, the couple set up an extensive display of historical photographs and artifacts, preserving and honoring their ancestral tradition bearers.5

Louise Bigmeat Maney was active in the western North Carolina crafts community. She participated as a demonstrator for the Southern Highland Handicraft Guild and, in 1977, was part of a delegation of Cherokee artisans who commemorated the groundbreaking of the Folk Art Center on the Blue Ridge Parkway near Asheville. Attending the ceremony was Joan Mondale, wife of Vice President Mondale. In 1998, Maney received a North Carolina Folk Heritage Award. She passed away in 2001 and was given the rare honor of being named a “Beloved Woman” posthumously by the Eastern Band.

Louise Bigmeat Maney with First Lady Joan Mondale |

Blackware pottery bowl by Louise Bigmeat Maney |

M. Anna Fariello

Biography excerpted from Cherokee Pottery: From the Hands of our Elders

Published by The History Press, 2011

1. Designs in Pottery by the Bigmeat Family (Cherokee, NC: Indian Arts and Crafts Board, 1979).

2. Arts and Crafts Board, Bigmeat Family; Joanne F. Vickers and Barbara L. Thomas, No More Frogs No More Princes: Women Making Creative Choices at Midlife (Freedom, CA: Crossing Press, 1993), 35; Joel Queen, “Integrating the Symbolic Past to Shape the Future of Cherokee Pottery” (thesis, Western Carolina University, 2009), 18.

3. Indian Arts and Crafts Board, Bigmeat Family.

4. Indian Arts and Crafts Board, Bigmeat Family; Vickers and Thomas, No More Frogs, 34–37; Indian Arts and Crafts Board, Documentary of Six Cherokee Artists, (Cherokee, NC, 1976).

5. Ibid.

\

\