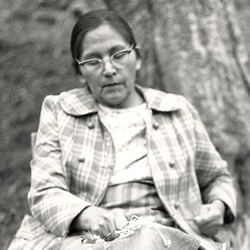

People: Rowena Bradley

Rowena Bradley (1922-2003) was the third generation of known basket weavers in her family . Both her grandmother, Mary Dobson and her mother, Nancy Bradley were accomplished at making baskets . Bradley is often cited as one of only a handful of Cherokee basket weavers who carried on the complex double weave technique in the 1930s and 1940s . Her baskets won numerous awards at the annual Cherokee Indian Fairs and an exhibition of her work was held at Qualla Arts and Crafts Mutual in Cherokee, North Carolina, in 1974.

Born in 1922, Rowena Bradley was raised on Swimmer Branch in the Painttown Community on the Qualla Indian Boundary, lands owned by the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians . As a child, she learned to weave baskets by watching her mother . She made her first basket somewhere around 1928, before she started school . She was just six-years-old . The youngest of eight children, Rowena Bradley lived with her parents until their death.

While the skill of Cherokee basketry was traditionally passed from mother to daughter, in many families, making baskets involved the entire family . Rowena Bradley’s father, Henry Bradley, Principal Chief of the Eastern Band, and her brother Jim, participated by gathering rivercane and digging roots for dye materials . Still the actual weaving of baskets was the province of women . Rowena Bradley, her sister Ellen Arneach, their mother, Nancy George Bradley (1881-1963), and their grandmother, Mary Dobson (b. circa 1857) were all basket weavers.

Neither Nancy Bradley nor Mary Dobson spoke English, but still managed to sell or trade their baskets locally, and many made their way into collections and museums . Rowena Bradley described the scene.

“I can remember mother weaving her baskets and when she had finished, she would tie them up in an old sheet and throw them across her shoulder and take them to Cherokee to trade for groceries.”

It was a long walk to town from Painttown, a community in the foothills of the Great Smoky Mountains. 1

Weaving baskets from rivercane is a tradition that goes back to prehistoric times, but suffered decline during periods of upheaval . In the mid-1700s, the Cherokee were exposed to diseases that devastated their population and, in 1838, they were forced—at gunpoint—to leave their ancestral homelands to embark on what has become known as the “Trail of Tears.&rdquo ; Bradley explained how that loss of continuity continued to affect her community decades later.

“At the time my mother was teaching me how to weave the double-weave baskets, there were only two people I know of who could do this type of basketry . Mother and a very old lady by the name of Toineeta who lived way up in the Soco community.” 2

The perceived erosion and loss of traditional skills was foremost in the minds of those who supported a regional Craft Revival, a movement to “revive” handcraft and preserve traditional forms.

While some dispute Bradley’s claim that there were only two living basket weavers who knew how to make double weave baskets, there is truth to her statement . Cherokee crafts traditions in general, and the making of double weave baskets in particular, declined as the 20th century progressed . By the 1930s, such skills were rare . Among the Cherokee, teacher and basket weaver Lottie Stamper re-popularized rivercane basketry through her public school teaching . Sarah Hill, in Weaving New Worlds: Southeastern Cherokee Women and their Basketry, lists a handful of women who made rivercane baskets at the time . These included Nancy and Rowena Bradley, Arizona Swayney Blankenship, Aggie Wilnoty George, and Rebecca Toineeta, the woman referred to by Bradley . Even with these knowledgeable basket weavers at work, by 1937, when Lottie Stamper introduced basket weaving to Cherokee schoolgirls, the knowledge and skill of the double weave had dwindled to a point where its future was in doubt.

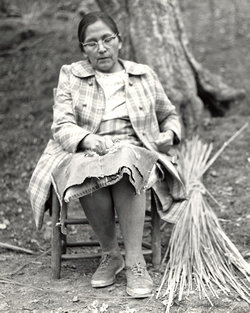

Rowena Bradley made a lifetime of baskets, distinctive in their design and fine craftsmanship . She explained the steps it took to prepare materials that went into a basket .

“You split [the rivercane] into quarters and then peel it . That makes narrow strips or withes . You soak it in water to make it limber and easy for weaving.&rdquo ;

Bradley used a pocketknife to quarter, peel, and scrape the cane . Adhering to tradition, she used native plants as dye materials to soak the cane and attain color . Like most Cherokee basket weavers, her palette came from plants common to the region . In describing Bradley’s process, journalist John Parris noted,

“Working from memory, she forms the strips into patterns and then into baskets of all shapes and sizes. Early in the process of a double-weave pattern, literally scores of withes seem to fly out in all directions.” 3

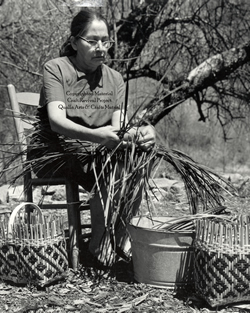

Bradley wove patterns that she learned from her mother but, like many creative artists, she also made up designs of her own . Her baskets were woven using traditional motifs, including Chief’s Daughter, Peace Pipe, Flowing Water, and Noon Day Sun. Bradley’s mother, however, did not use these names to describe her designs even though she may have made them . Bradley explained, “My mother never had no names or no meaning to her designs . She just made them.&rdquo ; But her mother’s patterns were ones Bradley remembered . “The designs I weave are the ones I remember Mother doing, or they are ones I have worked out,” she said . Unfortunately, Bradley did not know her grandmother, nor did she ever see any of her baskets. 4

All basket weaving patterns, whether passed down, or invented by a contemporary basket weaver, are the result of dyeing the rivercane before beginning to weave . Bradley used materials common to Cherokee rivercane basketry. The process of making a basket is matter of days or weeks.

“[To make baskets] out of rivercane, you split it into quarters and then peel it . That makes narrow strips or withes . You soak it in water to make it limber and easy for weaving….I make my own dyes from native roots and bark . I use butternut to make black and walnut to make brown . For light tan I use bloodroot.” 5

Butternut, black walnut, and bloodroot are commonly used along with yellow root . These plants, native to the region, are gathered and soaked in large pots . The color leaches out of them into the water . Afterward, the basket weaving material—rivercane, white oak, maple, or honeysuckle—is soaked to absorb the dye .

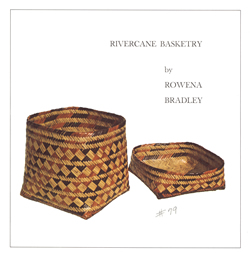

In 1974 Rowena Bradley’s basketry was celebrated with an exhibition held at Qualla Arts and Crafts Mutual in Cherokee, North Carolina . Funded, in part, by the Indian Arts and Crafts Board and the North Carolina Arts Council, the exhibition included 15 rivercane baskets, several of them double weave . By the mid 1970s, Bradley’s rivercane baskets were in demand . Of the 15 baskets in the show, three were in the permanent collection of the US Department of Interior’s Indian Arts and Crafts Board . The exhibit brochure mentions that Bradley earned numerous awards from showing her baskets at the annual Cherokee Indian Fair.

Steve Richmond, the exhibition’s curator, heralded Rowena Bradley’s work as a “new dimension of technical and aesthetic achievement.&rdquo ; In spite of these accolades, Bradley expressed doubt that the skill of basket weaving would continue to be passed on . “I will be honest and say that in a generation or two I think basket-weaving among the Cherokee will die out because the children don’t take an interest in it like they used to.&rdquo ; In contrast to her bleak assessment, Bradley expressed her own enthusiasm, “I learned how to weave baskets because I wanted to . I enjoy doing it and always have.” 6 Today, basket weaving among the Cherokee is on the rise, extending the tradition yet another generation.

Anna Fariello

Excerpted from Cherokee Basketry: From the Hands of our Elders,

Published by The History Press, 2009

1. John Parris, “Turning out the Double-Weave Basket,” Asheville Citizen-Times, circa 1974.

2. Indian Arts and Crafts Board, “Rivercane Basketry by Rowena Bradley” (Cherokee, North Carolina, 1974), reprinted in Mollie Blankenship and Stephen Richmond, Contemporary Artists and Craftsmen of the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians: Promotional Exhibits, 1969-1985 (Cherokee, NC: Qualla Arts and Crafts Mutual, Inc, 1987).

3. Parris.

4. Sarah H. Hill, Weaving New Worlds: Southeastern Cherokee Women and their Basketry (Chapel Hill: University of NC Press, 1997) xvi.

5. Hill, xvi.

6. Parris.